Blog

stories • happenings • adventures

This month’s “Ask an Ambassador” article comes from Joe Cruz. Joe has been bikepacking for more than 30 years on a wider variety of bikes and terrain than we can count. We asked Joe to tell us a bit more about his philosophy around bikepacking – specifically, how he thinks about what he carries. We hope you enjoy Joe’s take on lightpacking as much as we do!

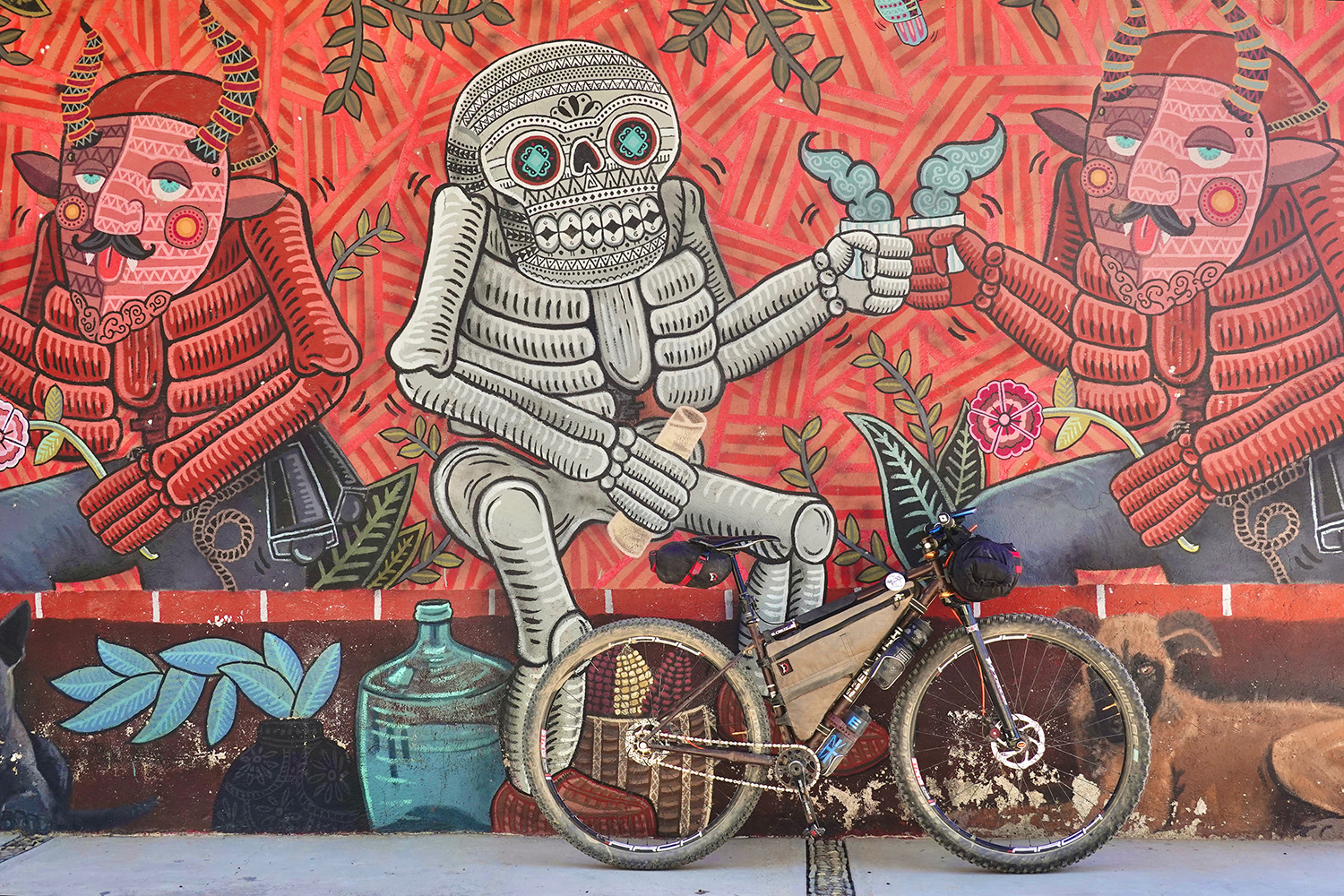

Photo by Joe Cruz

Photo by Joe Cruz

One of my favorite accounts of adventure is Journey to the Centre of the Earth. I don’t mean Jules Verne’s famous French novel, but rather the Journey written in the 1980s by the Crane cousins, Richard and Nicholas. It’s their story of riding bicycles from Dhaka, Bangladesh to the desert of Western China. This was their eponymous “center” of the Earth, i.e., the point on land furthest away from the ocean. They bikepacked in a spectacular ultralight style on custom Raleigh drop bar bikes fitted with 700c x 35mm tires—we’d nowadays call them gravel bikes—each carrying a pair of tiny panniers and that’s it. The Crane trip was exciting and ambitious and maybe a bit gloriously unhinged. There’s much to say about it on another occasion. But a tidbit that stands out to me is that one night before departing Lhasa, they committed themselves to reducing their already mind-bendingly light load even further. They cut off excess straps and buckles, they snapped their antibiotic pills out of the foil backed cards and consolidated them in a tiny bottle, and they looked at every single thing in their packs to see how it could be fine-tuned toward lightness.

Though I was traveling in a decidedly different bikepacking style on a fat bike, I had this Crane episode in mind as inspiration on a meandering six month trip in the Andes from Ecuador to Argentina a dozen years ago. One month in, I resolved to lighten my load. I’d at that point been bike touring for over 20 years and had plenty of experience packing judiciously, but I wanted to be even more nimble, fast, and light. So, for 30 consecutive days, I sought to refine my kit in some way each morning. It ranged from giving away my backpack to cutting off every label from every piece of clothing that I brought. Much of the exercise was whimsical and a form of amusing self-discipline. After all, saving grams by replacing every 4mm bolt with a 5mm one so I wouldn’t have to carry the 4mm allen key (yes, I did that) couldn’t possibly make any meaningful difference. That was when my commitment to light packing crystalized. My motivations back then were aesthetic rather than directly practical.

Photo by Logan Watts

Photo by Logan Watts

Of course, there are plenty of sensible pragmatic reasons for bikepacking light. A lighter overall bike means that the climbs are a little more forgiving or can be approached with a racier effort, if that’s your thing. If you’d like to use your dropper post, a lighter, smaller kit makes it possible to get away with a tiny seat bag. Likewise, fitting a front bag between the hooks on a drop bar bike is within easy reach. Hike-a-bike sections, or lifting the bike onto a boat or a bus or up the stairs of a hostel, are all easier. Moving faster with a light load is sometimes safer, as more ground can be covered to reach a resupply. Taking fewer things presents less of an image of consumption and wealth.

On the other hand, some kinds of lightness are foolish because they incur unacceptable risk. Traveling with less than you need can also be disrespectful to the people that you have to lean on to bail you out if you get into trouble because you neglected to bring something that you easily could have.

So, what I’m after is carrying not very much, yet just enough.

Photo by Search and State

Photo by Search and State

The thing is, common descriptions of what counts as light bikepacking are of limited help. Some people advise against “packing one’s fears,” by which they mean that many of us overpack because we’re irrationally worried about low-probability emergencies. If we were more objective about risk, the thought goes, we wouldn’t nervously bring so much stuff. That makes some sense, but risk assessment and tolerance are widely variable, so the slogan “don’t pack your fears” isn’t by itself particularly illuminating. One area where this advice can be handy, though, is in carrying food. In my experience both of myself and observing others, it’s overwhelmingly tempting to carry too much food on a bikepacking trip. So when I’m shopping initially or at a resupply, I do often wonder weather I’m being realistic about how much I can or will want to eat.

Others suggest bringing only items that will be used frequently, and that have multiple functions. That can be a handy preliminary heuristic. In the Andes, I asked myself while examining each item, “when is the last time I used this?” If it wasn’t recent, the thing would be a serious candidate for elimination. Yet for a lengthy trip, there’s a good chance that you’ll face many different kinds of terrain and weather that are clustered rather than steadily repeating. A puff jacket may stay stuffed in the seat bag for weeks in the lowlands, but be essential once at altitude.

Then there are bold quantitative definitions, where packing light is staying under, say, 15 lbs/7kg of gear and ultralight is under 10 lbs/4.5kg. I understand the impulse to sound objective, but offering a sharp dividing line really seems just an opportunity to brag. A fixed weight defining “light” might be useful only for some conditions, or presuppose a particular level of outdoor experience, or be so cost prohibitive as to be bourgeois foolishness.

I’ve given up on establishing a rule or a definition of light packing, and on my own trips I go back to what is for me the central idea of it, which really isn’t a point about gear at all. In my view, to really be somewhere is to go with as little imposition of your own strict demands as you can. To be insistent about the food or the weather or the rhythm of days, or about whether it shouldn’t be windy or hilly or hot is to expect a place to fit you rather than for you to be open to it. I bikepack to be receptive to the experiences that I will have. I want to be changed, even if only a little, so I want with me, figuratively speaking, as little baggage as possible. Instead of demanding that a place answer to my own expectations and finding either boredom when it does or disappointment when it doesn’t, I want to go with an empty heart to be filled.

This is mainly about spirit and psychology, of course. But the way I see it, the stuff you bring becomes at least a small part of the infrastructure of anywhere you go. When you have a lot of Things, they become too much of the environment, a literal manifestation of forcing the world to conform to your ultimatums, an expression of unwillingness to take it on its own terms. So I bring less so I can get more from my experience.

Photo by Joe Cruz

Perhaps I’ve succeeded in making that conclusion sound as poetic as I intend it, but maybe you’re reading this because you were hoping for something concrete and practical about packing light on a bikepacking trip. Honestly, though, that advice is hard to give. Packing light takes time and practice and self-understanding to find a way that works for you. Here, though, are a few thoughts.

You probably need less clothing than you think you do, even while still remaining firmly in the realm of the hygienic. I bring two shirts I can ride in, but I keep one clean for sleeping in. After a few days riding with the same shirt, I’ll (with some relief) switch to the clean one, timing it so that I can wash the one I started with. I do the same with thinly padded shorts, treating the clean pair to wear as underwear when off the bike and, again, for sleeping. Ditto with two pairs of socks. I wear the same pair of overshorts every day and carry very thin rain pants that can double as camp trousers. I additionally bring a long sleeved merino top, a light rain shell, and a hat. If it’ll be chilly, a puff vest or jacket and merino gloves will come along.

For camping, there are three bulky things that have to be reckoned with: shelter, a sleeping quilt, and a sleeping pad. My rule is that each of these should pack down to a size no larger than a cantaloupe. If I achieve that, they can all go in a front roll with plenty of room left over for the spare clothing. Alas, camp items this light and small are usually expensive, so that’s where I would concentrate my resources if I were trying over time to accumulate a light kit. Don’t overlook a tarp as shelter—and the pleasures of learning how to use one—if you travel in areas that aren’t plagued by bugs.

Photo by Sean Randolph

Photo by Sean Randolph

If you go into any outdoor gear store, the shelves are filled with gadgets and googaws for cooking and camp comfort. Consider the possibility that virtually none of this is necessary. You can make an alcohol stove from a soda can, you can carry a light 1 liter pot for all meal prep and consumption, and a plastic spoon will go surprisingly far. Better yet, delete some of those items by skipping cooking altogether and eating a cold meal for dinner while stopping for something hot in towns that you pass through during the day.

Sure, there will be lots more on your list. A tiny knife, a headlamp, a multitool, some resources for repairs, to name of few. If you deem something essential, bring the smallest, lightest version. Test not bringing one at all on a low stakes weekend trip to find out whether it’s as obligatory as you think. A camp chair, a Tenkara rod, a miniature coffee grinder, a sketch book: all of these things are nice to have and I’d bring them if they were central to the experience I want to have. But the way I travel these days, they are not. Something else is.

I wouldn’t dream of debating with you about whether you need a this or a that to have a successful bikepacking trip. My suggestion is a reframing of the question. Don’t ask whether you want or need some particular bit of stuff. Instead, ask what you might experience if you didn’t have that thing. Sometimes the negative valence of the answer is clear. For example, by not bringing a shelter when it’s likely to rain or snow—the Crane cousins didn’t have a shelter—you’ll experience being cold and wet. If that’s not what you’re wanting the landscape to impose on you, by all means bring a shelter! Other times, framing it in terms of what a place will offer yields a positive possibility.

The Cranes were using 2x cranksets, but didn’t have their bikes fitted with front derailleurs because they figured they could use a heel kick to downshift and reach down and pull up the chain to upshift. Did they gain anything by making their bikes lighter in this way? Maybe. Perhaps the inconvenient unusual motion required to tackle a steep climb gained a salience as they looked down to manually do this thing that would have otherwise been automatic and invisible. Perhaps that subtly changed their daily emotions to be more in tune with the mountains and valleys. I can’t say whether it made the Crane trip better or worse, and a single change like this can certainly seem frivolous and pointless. But the cumulative effect of many such decisions for me make a difference.

My reflections include: if I don’t bring a stove, I’ll eat more of the local food. If I don’t bring a third shirt, I won’t be distracted by having to make choices about my wardrobe and self presentation. If I don’t have the exactly right jacket for the weather, sometimes I’ll experience the day differently than what I thought I wanted. One last way of putting it, then, is that sometimes traveling with less introduces you to the imperfections of experience that constitute another and unexpected sense of perfection. That’s the attitude with which I set out on my trips these days.

—

Joe Cruz has been bikepacking for over 30 years and has in that time done almost every kind of tour on almost every kind of bicycle. He is the creator of some of the best known routes in the world, including ones in Slovenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Ecuador, as well as in his home state of Vermont. Joe is chair of the philosophy department at Williams College.

Joe Cruz is a philosophy professor, writer, and expedition cyclist. He has toured and raced bikes the world over. While Joe perfectly well likes rugged, remote, and challenging trips, his favorite bikepacking always includes a substantial cultural and historical element. He thus counts Tibet, Pakistan, and Peru as highlights. Joe and his wife split their time between rural Williamstown, Massachusetts and their beloved native New York City; his blog is Pedaling in Place. Instagram @Joecruzpedaling.